A former star of transparency and accountability in disability advocacy moved to the government side. His word has ceased being his bond

By Gideon Oladimeji

Talk is cheap. David Anyaele, the Centre for Citizens with Disabilities (CCD) founder, never acted like he believed this while he worked the fringes of power loop with his advocacy. His word choice and speeches cut to the chase most times in corruption talk shops then.

“Refuse to give or take bribes, gratification before carrying out services,” he wrote in one of his many press releases he spun around in 2019. “Always uphold the value of honesty, integrity, and transparency.”

On other occasions, he pumped up the disability community to force the government’s hand to release accountability information. “The government at all levels would only show concerns for PWDs if they quickly respond to requests for information with immediate steps and actions,” he once told an audience at a Freedom of Information Act stakeholder meeting in Lagos.

Emitting pep like this against corruption and opacity resulting from leadership incompetence came naturally to Anyaele then. Until he got a heave into Gov. Alex Otti’s administration in 2023. Clamming up has since become his shield whenever he gets a call to account for his stewardship.

The Fudge .The Sludge

For three months, the chairman of the Abia Commission for Welfare of Disabled Persons ignored ER request for clarification on his commission’s 2025-2027 Medium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF).

“I won’t give you,” he said. His rage at the manner of question took the better of him when ER first requested for information in March.

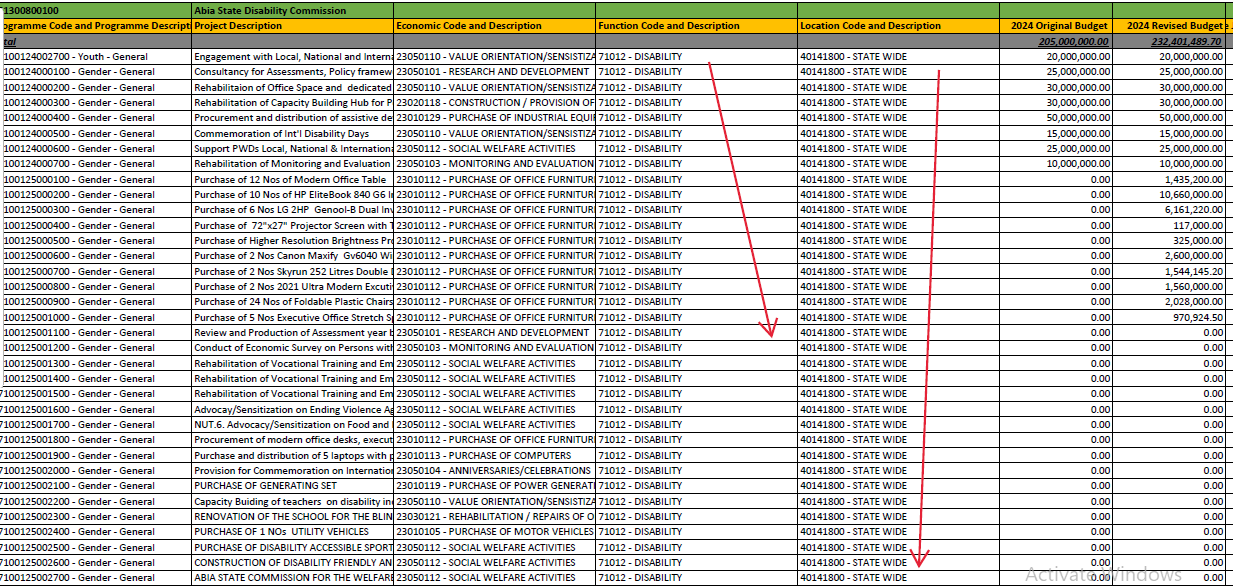

But the issue remains the elephant in the room: 35 projects, including the purchase of a N70-million vehicle, approved without a single location, all in one code; 17 of them got approvals last year; 10 different items, including computer notebooks, got lumped up as office furniture; one research contract split into two; and a slew of other items that hint of shadiness and shoddiness from the get-go.

Some members of the state’s disability community ER interviewed denied anything going on as disability-related capital projects in Abia. Rather than blame the commission, the state NAB chairman and his Albino Association counterpart made an excuse of its infancy.

A policy expert and a procurement consultant ER contacted to analyze Anyaele’s budget, however, spotted red flags. Both Siaka Salami and Jane (not real name) respectively agreed in separate interviews the chairman has accountability questions to answer, and the commission’s inexperience stands no chance as an excuse for opacity. A former state assembly’s procurement officer, Ned (not real name), however, dissented. An MTEF needs no belt and braces; so he chose to see no evil.

There has to be an annual budget (none except the summary) that flows from the over N455-million MTEF, one of the experts insisted.

Anyhow, Section 18d of Abia’s procurement law states any procurement shall be conducted “in a manner which is transparent, timely, equitable for ensuring accountability, and conformity with this law and regulations deriving therefrom”.

The ministry of women affairs, for instance, followed this in about 80 percent of its budget. Its purchase of a Hilux vehicle had a location: Umuahia North. Anyaele had nothing to say about the violation in his own commission when ER asked him for comments on the budget transparency.

He would not have deployed stonewalling to wing his way out of the state assembly during his budget defence. Nor would the tactic have helped him slip out of the state’s bureau of public procurement guardrails. He just didn’t have to worry. Neither of the oversight bodies cares about due process. And almost all the MDAs in Abia disregarded the law in a similar fashion. Except the Library Board.

They all made the best of a loophole they found.

35 projects lack locations

Section 13 of the law reels out the contents the record a procuring entity must have: contractor’s information; contract award dates; contract value; and procurement proceedings. No project location—despite section 20e demanding needs assessment during budgeting.

But for consultancy services, Section 47(1) c and g say procuring entities should indicate “the manner, place, and deadline for the submission of proposals”.

The ex-civil servant argued that section doesn’t apply to the Hilux, a generating set, laptops, and the rehabilitation projects to which the commission allocated about N125m. Maybe. But section 18d, on transparency and accountability, does, and proves a breach. With its four consultancy service projects lacking locations, the commission breached the provisions on either side.

A senior aide to the governor on due process didn’t respond to ER request for comment on the violation—punishable with five to 10 years in jail. The state’s budget office, according to him, has the responsibility.

The connivance at this level of procurement reaches down to tender and bidding. Anyaele, however, would not provide his commission’s past invitations to tender and other details. Those documents could have revealed the full descriptions, including locations, of all the projects tagged ‘statewide’. Something worse could have even reared up.

“This is quite disheartening,” said Salami, the Abuja-based public policy expert. “The whole scenario suggests that the budget seems to have been fabricated without thorough fundamentals.” He wondered how the commission priced the projects without locations.

It turns out the lack of location isn’t the only likely sleaze Anyaele and his team baked into their commission’s budget. There is also a “high concentration of procurement-related spend, vague description, and duplicated projects”, the procurement expert in Lagos observed. “There are multiple entries for rehabilitation, sensitization, and equipment without differentiation,” she noted.

ER uncovered two of such line items tagged Research & Development (R&D). The first—Consultancy for Assessment, Policy Framework, located “statewide”—got N25m as 2024 allocation, and N5m in 2025. The commission described the second R&D, also statewide, as Review and Production of Assessment Year Book. It got an allocation of N3m in 2025, and another N3m for its climate change relevance. No allocation last year.

Broken down, the first eight items of the commission’s budget got N205m in allocation in 2024. Purchase of Assistive Devices got the highest, N50m, then; Engagement with Local, National, and International Bodies got N20m, the lowest of the 8. In 2025, the same set of projects came up. Engagement got N16m, the highest of the eight. Along with 6 others, the allocations add up to N58m in 2025.

One of the recurring projects is Rehabilitation of the School for the Blind. Despite its known location at Afaraukwu in Umuahia, the budget planners still tagged it statewide. It got no allocation in the 2024 revised budget, but some make-overs took place still. School Principal Bernadette Nnena told ER in July the state mended the school fence last year. Another source in the know revealed an NGO, the International Ministers Fellowship, supported in the rehabilitation. “They rebuilt the school fence, security boot, one of the hostels with a leaking roof,” the source said.

Rehabilitation in one form or the other continues on the school premises, though not on account of the commission’s budget. A member of the state assembly Hon. Anthony Chinasa is building a six-block structure there as his constituency project.

In spite of all that is going on there, the disability commission still allocated N10m to rehabilitation in 2025.

According to the procurement consultant, all these suggest either poor planning or bottlenecks in implementation. The budget planners’ sloppiness even sticks out more in the internal spending: its allocation of N75m, the highest in 2025, to buy a utility vehicle that has no location to park; even office equipment like a generator set and a projector screen have no trace. Just statewide.

“This is not a sophisticated policy mistake,” Salami said. It’s not much about the MTEF either. “It’s a basic planning failure.” According to him, the framework still operates under the procurement law, and cannot serve any implementation or monitoring purposes. Using it makes impossible to monitor any of the commission’s 35 projects that makes it to award and execution. “This is a known loophole for misappropriation or fictitious contract award.”

Ned insisted nothing is amiss despite the provision of the law. “It’s when procurement wants to take place that location and other stuff become most essential,” he told ER. But the retiree agreed with Salami on locations determining project costs. “Location may impose some hidden costs that may hinder a project,” he added, ignoring the needs assessment and the accountability issues the deliberate omission creates, which Salami hammered on. The retiree also overlooked the other MDAs which described many of their project locations in the MTEF—before implementation.

The Fantastic Five

Many could have wondered what started off the two-year-old commission on this footing. Under Anyaele, its pioneer chairman, the commission has presented and got two budget proposals approved, ambiguities and all. So much for the experience and efforts of a team of five: Anyaele on top of the food chain; four others follow. No particular order of pay grades or job specs. In fact, the commission can boast of no organogram up till now.

That casts no doubt on Anyaele’s experience in disability advocacy—even if he now spurns freedom of information, and secretes accountability data. For effect, he likes to wave his badge of 23 years in advocacy, his pivoting from championing the amputee cause to that of citizens with disabilities. His organisaton’s three offices across the nation have cranked out no fewer than 21 reports on accessibility, equal participation, inclusive education, and disability laws implementation. Little, though—by way of administrative competence or policy grasp, beyond cluster leadership— is available to most of his team.

Team leader Anyaele

Critics insist inexperience is no reason to spare the commission the rod for any proven budget shenanigan.

Some disability cluster leaders in Abia chose their words in responding to ER interviews. Still their views meshed: Anyaele and his budget planners go big on proposing and executing all kinds of projects but capital ones.

“I know it has been doing a lot in sensitization and inclusion advocacy: roadshows, media campaigns, leadership and capacity building training,” Abia NAB’s chairman Okwudiri Williams told ER. His counterpart in the Albinism Association of Nigeria, Eyinanya Nwosu, also confirmed the glut of sensitization and leadership training.

So the Anyaele team annually splatters the commission’s budget with duplications of those jamborees. Five items of such nature found their ways into the 2024 and 2025 budgets, as though he knew how much of such projects the community wants.

The Uninformed Losers

Anyaele knows certain things for sure. Like the estimate of the PWD population his commission is responsible to: over 400,000 he once attributed to a UN report figure. What he fails to know is funding disability holiday celebrations and grooming leaders statewide don’t cut it for many of the PWDs.

“I have not seen any capital project the commission has embarked on—not to talk of project locations,” the NAB chairman said. “If there is any, the commission has not made our clusters aware of it.” For Nwosu, nothing compares with funding infrastructure. “And the commission needs to do more of that, and make us aware,” he said.

Disability commissions mostly have no mandate or budget to run as free-standing capital-project machines. Both cluster leaders had no idea of this. They didn’t even see the commission keeping them in the dark on whatever it will spend the over N400-million budget if it gets funding. They would rather speak for the planners who smudged the budget with vagueness. “We know this is the first budget—if I am correct—the commission would get approved since its establishment at the tail end of Gov. Ikpeazu’s administration,” the NAB leader said.

But the experts saw through the commission’s sleight.

Public projects without clear locations, Salami noted, cannot be transparently tracked or audited; and most infrastructure projects, by nature, are localized.

“It then becomes impossible to tell which communities are being prioritized—or neglected,” he told ER. “This will undermine equitable service delivery for persons with disabilities across urban and rural areas.”

Salami also disagreed with the cluster leaders on the commission’s inexperience. If anything, he insisted, new institutions need tighter support and clearer rules, not looser ones.

The Lapdogs

Anyaele and his team have set off confusion by letting 35 projects float about with no place to anchor. A perfect smokescreen now smolders to blur the possibility of equitable service delivery. And this is happening under the state’s public procurement bureau’s watch—and its procurement law.

The commission has flouted a direct provision of the law that enforces locating a project. Nobody bats an eyelid yet. Nothing then prevents it from ignoring the internal check for which the law also provides.

Each procuring entity, by law, must have a procurement department or unit. An accounting officer in charge, according to the law’s section 22, ensures a planning committee adheres to the spirit and letter of the law. ER could not confirm from Anyaele if the commission has one. In any case, an accounting officer can’t help failing in implementing these sorts of budget items. The alternative is to join in the connivance.

The consultant suggested civil society organisations and cluster leaders actively monitor the commission’s project delivery. That makes sense—since the state assembly and the procurement bureau have failed. But Anyaele, with his CCD ownership, is no slouch in civil society politicking. And, in that circle, a network of friends doesn’t rock the boat by asking their buddies in government difficult questions.

That trade-off comes with the terrain. Critics may reel in pain over this absence of watchdogs to bark at the procurement malpractice going on in Abia’s disability affairs. It’s the reality anyway.

And it gets more complicated when it comes to bringing the law to bear on the likely perps: the accounting officer, the procurement committee, and others, including the chairman on whose table the buck stops.

Section 61(3) of the law provides that only the state, through the attorney-general, decides who it prosecutes for what. Any PWD alleging what the consultant called a breach of statutory law in awarding 35 projects without sites may bring a petition. It just may not stick.

Only a bad fallout—with his paymasters—can sweep Anyaele into facing legal scrutiny for his commission's malpractice.

That seems a long shot, as talk goes.